Falling from the back of a horse, understandably, hurts! The 1.5+ metre drop to the ground can cause life changing injuries for professional athletes and hobbyists alike. Such falls are especially severe in cases where riders suffer a blow to the head, causing a concussion or worse. As Sports Engineers, we can help reduce such injuries by introducing new technologies and more effective headgear. But first, we must understand what we need to protect against.

Athlete falling from horseback during elite level event [1].

Certifications are in place for equestrian activity which ensure a helmet is fit for purpose. In Great Britain, it is a requirement by the British Horse Society that helmets used in competition are approved by the British Standard product approval specification (PAS015:2011) [2]. This procedure involves a freefall drop of a metal headform (human shaped dummy head) onto flat and curved surfaces. However, like all specification/standard test procedures, this method must simplify the real-world conditions.

Research has recently looked towards capturing and recreating the conditions leading to horse riding brain injuries, to then advise what helmets should adequately protect. These have mostly involved use of motion capture (with either video data or movement sensors), computer simulation, and mechanical recreations to quantify head impacts and predict injuries [3].

Example capture of a fall from horseback in racing activity, recreated with a computational model [3].

However, when we recreate real-world situations experimentally (either mechanical or computational) we make assumptions that sometimes discard important factors that would contribute to injury. An example of this, which often happens in head impact tests, is the disregard of a human neck that limits how the head can move following impact.

Diagram of test device.

At Sheffield Hallam University, we have an Anthropometric Representative Test Device (ATD), or as they’re commonly called ‘Crash Test Dummy’ [4]. This has been used to better understand head injuries for riders falling from horseback, while maintaining human-like falling behaviour [5]. This allows us to explore the fall onto a concrete surface with conditions as close to a human falling as possible, without using human volunteers (VERY unethical!). The ATD was positioned on a platform 1.75 m from the ground, pushed at the side, to then fall to the ground at an average speed of 4.5 m/s (10 miles per hour), with no helmet on. We managed to capture this fall using high-speed cameras, which would take 2000 images per second. We also collected how the impact with the floor would create a force that accelerates the ‘human brain’ in a straight line (linear) and in a circular motion (angular). We used these accelerations with equations for predicting how severe the injury is likely to be [6].

Experiment set up of an elevated ATD (‘Crash Test Dummy’) to simulate an unconscious fall from horseback. Also, high-speed camera footage a single trial showing the ATD in colliding with the concrete floor at 10 miles per hour.

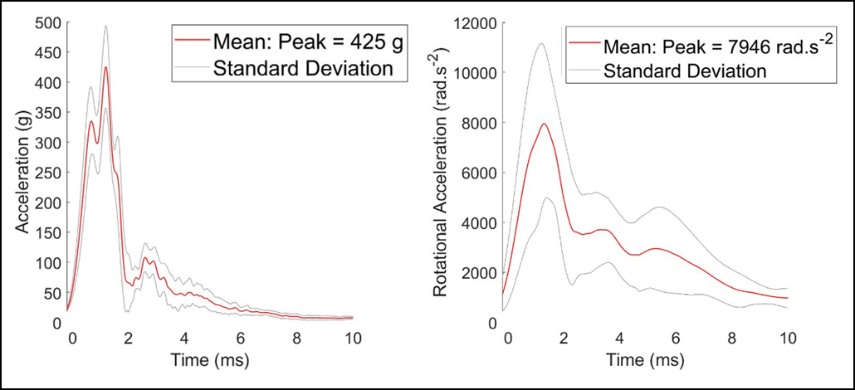

What we created were time history traces for these accelerations that showed all major forces occur well within a window of only 10 milliseconds (ms). The linear accelerations are in the range to almost guarantee a severe brain injury (Diffuse Axonal Injury or a potential fatality) and angular accelerations are on the verge of possible mild brain injury (mild concussion).

Acceleration time histories (linear and angular) for impacts.

These findings are some early results in a much wider study looking at the conditions of severe head impact scenarios. We wanted to maintain a high level of biomechanical representation, though this required the sacrifice of repeatability. These acceleration time histories can be used to inform/validate future computer and mechanical recreations of head impact when falling from horseback. Ideally, this work will be extended to simulate a galloping horse and include other surfaces for equestrian activity, such as turf and sand.

As mentioned, this work is the part of a wider brain injury study. For more information on this Wills University profile and LinkedIn.

[1] Horse and Hound, 2019. Concussion in horse riders — how to recognise it. Accessed August 2023. https://www.horseandhound.co.uk/features/concussion-horse-riders-recognise-680014

[2] PAS 015:2011: Helmets for equestrian use. (2011). British Standards Institute.

[3] Clark, J. M., Adanty, K., Post, A., Hoshizaki, T. B., Clissold, J., McGoldrick, A., Hill, J., Annaidh, A. N., & Gilchrist, M. D. (2020). Proposed injury thresholds for concussion in equestrian sports. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(3), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.006

[4] Humanetics Innovative Solutions, Inc. https://humaneticsgroup.com

[5] Dawber W., Foster L., Senior T., Hart J., (2023). Traumatic Brain Injury Predictions Amid Equestrian Activity with Realistic Biomechanical Constraints. IRCOBI Conference. Cambridge.

[6] Hernandez, F., Wu, L. C., Yip, M. C., Laksari, K., Hoffman, A. R., Lopez, J. R., Grant, G. A., Kleiven, S., & Camarillo, D. B. (2014). Six Degree-of-Freedom Measurements of Human Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 43(8), 1918–1934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-014-1212-4