parkrun (usually written with a small ‘p’) is 19 years old: still a teenager but with a good idea of what it wants to be when it grows up. In this article, I describe how parkrun has evolved during the first quarter of this century into one of the most important public health initiatives in the world.

A first parkrun

Ben Heller asked if I wanted to do parkrun. “What’s park run?” I asked.

“It’s new,” he said. “Park run – it’s a run in the park; that’s its name, park – run.”

“It’s free,” he added, for impact.

I frowned as he repeated the words park and run as if it would bring clarity. “Park run – park-run – parkrun.” The words became meaningless.

“I can run in the park whenever I want,” I said. “I don’t get it – what’s the point again?”

“It’s five kilometres and you get an official time – it’s a bit like a time trial; we can use it for training.”

Even as a researcher into sport I was dubious and played for time: “When is it exactly?”

“Saturday at nine”.

In the morning? On a Saturday? On my lie-in day? “I’ll think about it”, I muttered non-committedly.

As the weeks passed, I heard others talk about parkrun – how great it was, how much fun it was. People shared their times and commented on who they’d seen there. Repeatedly, they asked me if I’d done it: “You’d enjoy it”, they said.

Finally, after a month I gave in. I could say I’d done it and then they’d leave me alone.

I registered online the week before and fought valiantly with the printer to produce a personalised identity card with a barcode. I had no problem getting up on the Saturday – the nerves woke me. I cut out one of the eight barcodes from my printed A4 sheet and jogged down to the park with a small backpack bouncing around my shoulders; taking no chances, it carried a waterproof, hat, gloves, water and a banana.

I had two fears: one, that I wouldn’t know anybody and, two, that I’d come last. I’d never been particularly good at sport: “enthusiastic” said my school reports. I think if I’d been a dog, I’d have been a red setter, tongue lolling and legs flailing as I chased imaginary birds.

I arrived at the park, carefully timing my appearance to minimise standing around so that I wouldn’t look like Billy-no-mates. It was surprisingly busy, a few people already lined up and ready to go – a colleague waved at me and I waved back. Ryan Amos – the event director – wore a bright tabard and was drawing people towards him: “Briefing for first timers!” he shouted. I shuffled over to join them.

He explained the route around the park, that it was two laps and that the park didn’t belong to us – “so be courteous to others”. Once we’d finished, someone would give us a token which a volunteer would scan along with my barcode to match them together; the results would be online later that day. I pulled the barcode out of my pocket – it was already battered. Oh well, I wouldn’t be needing it again.

I threw my black kitbag onto a small pile of identical black kitbags, wondering if I’d ever see it again, took a deep breath and wandered over to the start. The front seemed to consist entirely of skinny 20- or 30-somethings in vests, fiddling with their watches. I walked down the queue and found Ben about a quarter of the way along. I joined him, feeling very much a fraud.

“You made it!” he said cheerfully.

I looked around: dozens of people, as many women as men. There were just a few oldies like us. “They look a bit fast,” I said, nodding at those in front, and shuffled backwards down the queue.

Ryan stood with a stopwatch at the head of the runners. WIthout warning, he shouted, “Go!” (this would be his style for years to come). The vests shot off into the distance while I lumbered past the start. After a minute, I cursed: my shoelaces had come undone. I tied a double knot and sprinted on, surprised by my anger. I quickly ran out of steam and slowed down to a plod. Two laps later I attempted another sprint – this time through the finishing line.

Gasping for breath, I stopped my watch and someone handed me a little plastic token. I saw a volunteer looking expectantly in my direction and I shuffled over. “Barcode?” she said. I pulled the damp bedraggled paper out my pocket and she aimed a small electronic device at it so that a red laser line quivered across its black stripes. She waved the device around as the paper started to wilt and we held our breath. She tried different angles and distances then, suddenly, it bleeped. She smiled and we breathed out.

“Token?” she said, putting out her hand. I passed it over and with a flash of red, the scanner bleeped again.

She looked up and grinned. “Well done, Steve”.

I smiled back and wondered how she knew my name. I looked down at my barcode and there it was written just above my number. Hmm, I’d have to cut out another one and put it in sticky-backed plastic. I should also double knot my shoelaces next time.

With a surprise, I realised I was coming back.

parkrun’s evolution

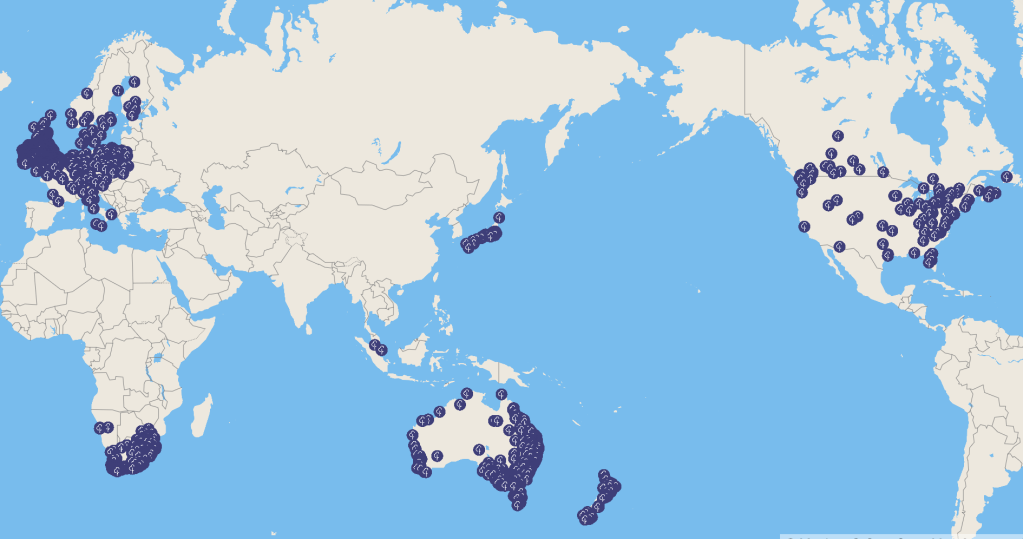

By the time I did my first parkrun, it was already five years old, having started way back in 2004 by Paul Sinton Hewitt at Bushy Park in London. Initially, it was a time trial for anyone who wanted one, but transformed into parkrun during 2008 and from then on spread across the UK and the world – it’s now in 22 countries worldwide with more than three hundred thousand parkrunners each weekend, supported by tens of thousands of volunteers.

Looking back at the results of my first parkrun (Endcliffe Park, Sheffield, 14 August 2010), there were just 72 runners: the first finished in just under 16 minutes, the last in 37. Thirteen years on, it has been transformed and there are regularly more than 600. While that first one felt very much like a race, it now feels more like a social event interrupted by a run. Of course, there are still the vests sprinting off at the front, but behind them are gaggles of families and friends. I have to shoe-horn myself into my regular slot somewhere just ahead of the middle (I still arrive only just in time). One of the biggest changes is the age of the participants. There are now more children at Endcliffe Park than the totality at the event 13 years ago, and the oldest are in their 80s.

Stand at the start of a parkrun and you can see the whole world go past: mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, grandparents, babies in buggies, yappy dogs, and friends chatting away merrily. Almost weekly, there will be someone in fancy dress wearing a ribbon with the words ‘bride’.

You don’t have to worry about being last anymore because there is always a volunteer tail-walker. The fastest time is about the same as 13 years ago but the longest is now over an hour. Parkrun HQ are really proud that the average time has gone up by more about a third from 22 to 29 minutes. Why would they be happy that people have got slower? Simple: it reflects parkrun’s three-pronged success story. First, there are now so many people that it can take a half a minute just to get across the start. Second, parkrun has been going so long that there are a quite a few regulars – like me – who have got older and slower. Third, and most significantly, parkrun now attracts many who are new to physical exercise (or, at least new since they left school): these are also slower and there are now park-walkers too.

Why parkrun works: what the research tells us

What is it that attracts so many people to parkrun? Firstly, there’s the practicalities: it’s free, it’s at the same time, on the same day, in the same place and with the same set-up. Take your parkrun barcode to any event in the world and you know exactly what to expect. Importantly, there’s no pressure to take part if you don’t want to. As parkrun grew in size, its mission evolved from a parkrun for anyone who wants one to a healthier happier planet. This reflects the realisation that with the change in the demographic of parkrunners, fewer were interested in the performance aspect and more interested in the potential health benefits.

A decade ago, parkrun set up its parkrun Research Board: in 2015, I was lucky to be asked to chair it and base it at the Advanced Wellbeing Research Centre. Its main task was to coordinate those around the world (academics mostly) who saw parkrun as a rich source of participants for research. Since its inception, the Board has reviewed around 240 proposals with a third of them approved. Along with seven PhDs, this research is worth in excess of £1.5m.

These efforts have produced more than 75 full journal articles, with at least 30 of them open access: themes include social prescribing, mental wellbeing and the impact of volunteering (see the Virtual Article Collection below). In total, the articles have been downloaded around 120,000 times and around half of parkrun papers are in the top 5% of papers for engagement by the general public (as measured using the Altmetric Score); pretty good going for academic research.

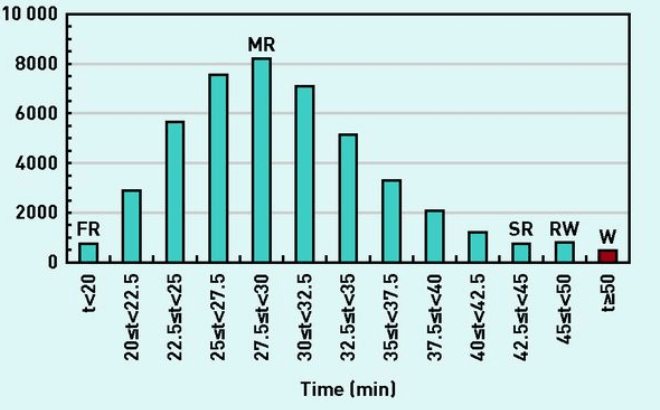

To answer the question of why parkrun works, you first need to ask who parkrunners are. We answered this in a paper published in the British Journal of General Practice called parkrun and the promotion of physical activity: insights for primary care clinicians from an online survey. We showed that most parkrunners ran a time between 27.5 and 32.5 minutes (see Figure) with smaller representations of front runners (FR), slower runners (SR), runners-walkers (RW) and walkers (W). There was an almost equal split of males and females for median runners (MR); the front was dominated by males (as they are faster) while the rear was 80% female.

Unsurprisingly, motives for first turning up vary (encouragement by others, health, training etc). At the front, these tended to be performance related (e.g. getting a good time, training for an event); at the back this tended to be health related (to improve mental health, to improve or manage a specific health condition). Around 20% were walkers, runner/walkers or slow runners.

While motives for taking part in the first place depended upon gender, age and running time, the benefits were broadly the same: improvements to fitness, health and a sense of personal achievement. Importantly, it was the social aspect of parkrun that seemed to bring people back week after week.

A grown up parkrun

Given parkrun’s apparent success, where does it see itself going? What does it want to be in five years time? In its five-year strategy, parkrun has this vision: to improve the health and wellbeing of as many people as possible, no matter who they are, no matter where they live.

By the time you read this, the 100 millionth parkrunner will have had their barcode scanned: in the next five years this should more than double. The clues to what parkrun will do are embedded in its vision: continued growth and engagement by people from all communities, regardless of who they are. This latter point is a criticism I ofter hear pointed at parkrun – that it’s just the usual people, those who would’ve run anyway. This is unfair: our research shows that many parkrunners are those with long-term health conditions looking to improve their quality of life and have returned to physical activity because of parkrun. Admittedly, participation in deprived areas is lower than in more affluent areas, but asking parkrun to solve wider determinants of health such as education, employment, security and environment is just unrealistic.

Looking at the last 19 years, parkrun has grown in an agile manner. As most youngsters do, it hasn’t always got things right, but it has always tried to do the right thing: it is this ethos that makes parkrunners so loyal. The research shows that parkrun improves large numbers of people’s lives through physical activity where other initiatives have struggled. Because of this, I feel that parkrun is probably the most important public health initiative relating to exercise this century. In an increasingly fractious world, parkrun has made it just that little bit healthier and happier: I expect this to be even clearer in five years time.

—

Steve Haake is Chair of the parkrun Research Board. The opinions in this article do not necessarily represent the views of parkrun.