To improve product performance the Sports Engineering Research Group (SERG) at Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) work to better understand sports equipment and its interaction with users as well as the environment. We research whether something is possible and develop engineering solutions to fulfil product needs using fundamental physics, experimental methods and modelling techniques. We utilise user-centred design to push the boundaries of innovation in sports equipment and validate our interventions using advanced measurement systems.

In conjunction to improving equipment and product performance we also focus on injury prevention. By understanding the causality of injury we can physically replicate and computationally simulate representative scenarios. We do this to understand injuries occur to all parts of the human body and through innovation we find novel solutions to mitigate injury risk. Through this work we helped to develop products, evolve materials and set new test standards.

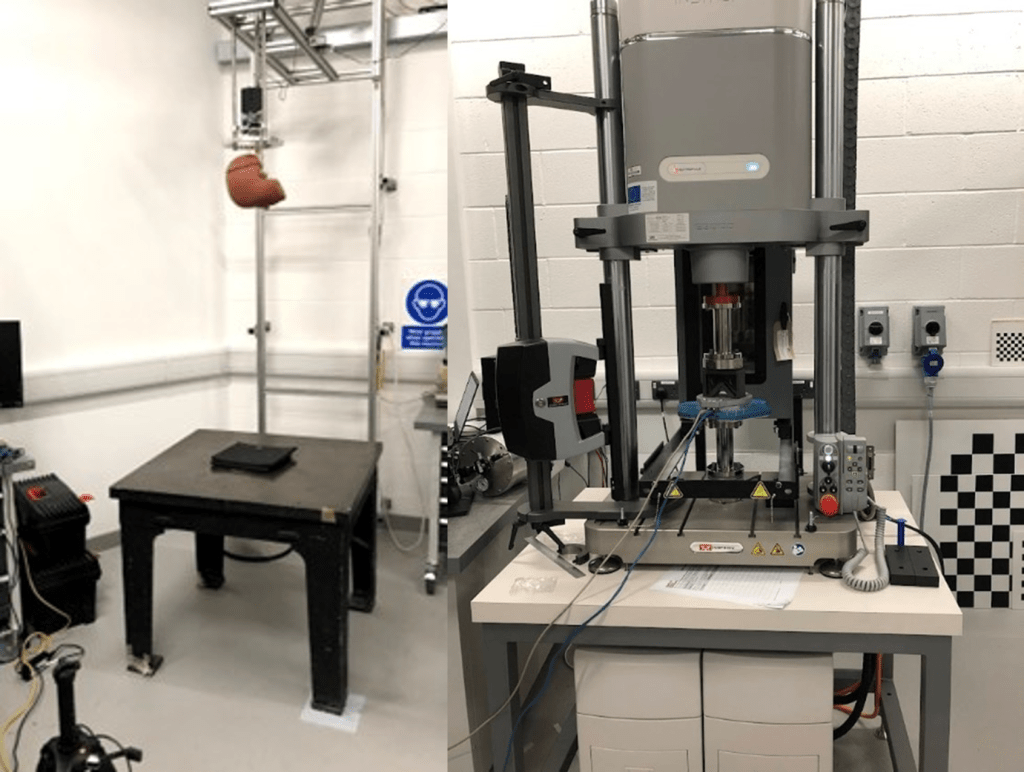

The workshops and labs at the Advanced Wellbeing Research Centre (AWRC) house a range of our test equipment including a drop-rigs, Instron quasi-static and dynamic test machines, impact simulators, ball projectors and a crash test dummy (ATD, Anthropomorphic Test Device). We augment these with a range of measurement systems including high speed video, Tekscan pressure sensors, custom timing systems as as well as inertial measurement units (IMUS).

The importance of sports protective equipment

Sports protective equipment plays is important role in safeguarding all sport participants from injuries. Whether it is the elite ice hockey player, the Sunday league footballer, or recreational cyclist there is a range of sports equipment which helps reduces injuries when a mishap occurs such as a collision, fall or ball to the nether region. This sporting protective equipment also allows these participants to carry out their sporting action with limited impact on their performance.

Sports protective equipment is commonly made up of padding and sometimes some form of hard layer which dissipates point loads over a larger area. Typical examples include shin pads, helmets, padded shorts, shoes, face and neck protectors, gum shields, kneepads, googles, cricket boxes and so on. Each piece of sports equipment is often designed specifically for the sport or activity which they are intended to be used in. Also, equipment is designed for the person using them. i.e. a child’s cycling helmet is ideal for a child riding a bike.

The ongoing improvement and development of sports protective equipment is reliant on rigorous testing protocols, which themselves are also in continuous development. Testing of sports protective equipment can occur through the design stage as well as for continuous evaluation when the equipment is in use.

What is the significance of the testing of sports protective equipment? Why do we need to do this? We are going to explore equipment testing and its vital role in ensuring our safety as well as maintaining performance.

Types of Sports Protective Equipment

Various sports necessitate different types of protective gear tailored to the specific demands of the activity. Helmets used to protect the head are common where a head impact is possible, such as cycling, team sports such as ice hockey and American football, field hockey goal keepers as well as a cricket batter. Shin pads are used across a variety of sports too, such as football, field hockey and martial arts. Gum shields again are used across a wide variety of sports such as rugby and boxing. These are just a few examples of the diverse protective equipment used across different sports disciplines.

The Role of Testing in Sports Protective Equipment – What do we do at the Sports Engineering Research Centre? Testing sports protective equipment involves a meticulous evaluation process aimed at assessing its durability, impact resistance, comfort, and overall effectiveness in preventing injuries. These tests often include simulations or replication of real-life scenarios/impacts, material characterisation, impact absorption tests, and ergonomic evaluations such as comfort, fit and temperature sensitivity.

Athlete assessment and scenario recreation – how do we know what the equipment needs to withstand? To design sports protective equipment, you first need to know what you are protecting from. This has been difficult in the past as measuring the dynamics of injurious scenarios has been difficult and subjecting participants to the testing of sports protective equipment in a lab is unethical. Recently more novel solutions such as the analysis of infield video data and infield sensor technology such as instrumented mouth guards can be used to gather data when an injury occurs. Additionally, anthropomorphic test devices (ATD) aka crash test dummies, are used to simulate a human body during an impact test and sensor data gathered according. Data gathered in this way can inform designers of sports protective equipment what the dynamics and forces of impacts they need to protect wearers from.

Modelling: Sports protective equipment is often designed using computer aided design and these designs are often subjected to finite element modelling techniques to gain an idea of how effective they will be in preventing injuries. Prototype designs are taken forward to manufacture and further physical testing is then carried to explore the validate results.Within the Sports Engineering Research Group we have an experienced design and modelling team which help manufacture with this stage of the process.

Impact Testing: This is crucial, especially for helmets and padding, involving controlled impacts to assess how well the gear absorbs and disperses force. We do this in a number of ways including drop tests, swinging pendulum tests and projectile testing ,i.e. firing projectiles at equipment.

Durability Testing: Manufacturers subject protective equipment to rigorous wear-and-tear simulations to ensure they can withstand the demands of continuous use in sports environments. Within the Sports Engineering Lab we have climate chambers and devices to repeated load equipment to failure to explore the durability of designs.

Material Analysis: Evaluating the materials used in protective equipment to ensure they meet required safety standards for strength, flexibility, and resilience. We do this using material testing rigs such as our Instron tensile/compression/torsion testing machine.

Comfort and Fit Assessments: Equipment must not only provide safety but also be comfortable and properly fitted to ensure freedom of movement without compromising protection. In field athlete testing is the only real way an accurate assessment of the fit, durability and comfort users of equipment experience. Survey tools are an effective way of gathering this type of data.

Crash test dummy and equipment: At the Advanced Well-being Research Centre, the Sports Engineering Research Group has extensive design testing and manufacturing facilities. Below are some examples of the type of equipment used to test Sports Protective equipment.

Figure 1: Advanced Wellbeing Centre – Design Engineering lab setup for ATD projectile testing

Figure 2: Advanced Wellbeing Centre – Design Engineering lab – drop rig and Instron equipment

Regulatory Standards and Certification: Various regulatory bodies, such as the British Standards Institute, International Standards institute as well as the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE), establish safety standards and certification requirements for sports protective equipment. Equipment that meets these standards receives certification, assuring athletes, coaches, and parents of its safety and efficacy. However, not all equipment is required to pass these standards and standards can vary throughout the world. Within the Sports Engineering Research group we replicate test standards for a variety of different sports equipment within our testing lab.

CASE STUDY: Rethinking helmet standards in Ice Hockey for concussion prevention

Ice hockey has one of the highest concussion rates in sports and ~90% of reported concussions in ice hockey are the result of collisions with other players. Collision type impacts, that can produce high strains in the brain, are characterised by lower accelerations and higher impact durations than falls onto the ice, although only falls onto the ice are represented in certification standards. Helmet evaluations in peer-reviewed literature require a variety of laboratory equipment. A simplified test protocol, based on impacts which commonly cause concussion, could facilitate representative helmet testing by more researchers, while increasing the feasibility of modifications to certification standards.

Figure 3: (A) Free-fall drop test setup, (B) Front site, flat MEP pad surface just before impact (C) Front site, oblique 72 mm foam during impact with FrontBoss («) and RearBoss (●) impact sites marked.

A 50th percentile male Hybrid III crash-test dummy head form was fitted with IMUS and tested with four different ice hockey helmets, with typical materials and technologies. Linear acceleration and angular velocity were measured during impacts onto different surfaces at different angles using a free-fall drop test. Video footage was recorded to explain some impact events and measure impact velocity. Drops were carried out from a height of 1m on to a representative range of locations resulting in an impact velocity of 4.5m/s, similar to standard procedures and common test protocols in literature, resulting in an impact energy of 51.3 – 53.8 J. Impact duration and peak linear and angular acceleration were used as measures of helmet performance.

The highest accelerations and shortest impact durations were produced during impacts onto rigid surfaces. With increasing impact surface compliance, the peak accelerations decreased while impact durations increased. A broad range of head form kinematic responses during impact was obtained, changing with impact surface compliance and surface orientation. The relative difference in kinematic values between helmeted and non-helmeted impacts decreased with increasing impact surface compliance, agreeing with previous work. The linear and angular accelerations were similar to the characteristic kinematic responses of ice hockey head impacts. These findings suggest that the free-fall drop test method can replicate collision type head impacts in ice hockey.

Conclusion:

Sports protective equipment serves as a critical line of defence for all those taking part in sport, minimising the risks of injuries while allowing them to perform at their peak. Rigorous testing processes are the backbone of ensuring the reliability, safety, and performance of these protective tools.

The landscape of sports protective equipment is constantly evolving, driven by advancements in materials science, design, technology, and a deeper understanding of athlete biomechanics in relation to injurious scenarios. Continuous testing, research, and innovation are pivotal in developing more effective and efficient sports protective equipment to keep everyone as safe as possible and enhancing well-being during physical activities.

The Sports Engineering Research Group are helping in all areas of sports equipment design and development – please get in touch with us if you have any enquiries on this topic or other areas covered in this blog. For more information about work we do in SERG check out our website, our annual review or our MSc Sports Engineering course.

If you would like to learn more about this topic, please check out our relevant publications:

Haid, D., Foster, L., Hart, J., Greenwald, R., Allen, T., Sareh, P., & Duncan, O. (2023). Mechanical

metamaterials for sports helmets: structural mechanics, design optimisation, and performance. Smart Materials and Structures, 32 (11). http://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665x/acfddf

Duncan, O., Foster, L., Allen, T., & Alderson, A. (2023). Effect of Poisson’s ratio on the indentation of open cell foam. European Journal of Mechanics – A/Solids, 99. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2023.104922

Haid, D., Duncan, O., Hart, J., & Foster, L. (2023). Free-fall drop test with interchangeable surfaces to recreate concussive ice hockey head impacts. Sports Engineering, 26 (1). http://doi.org/10.1007/s12283-023-00416-6

Duncan, O., Allen, T., Birch, A., Foster, L., Hart, J., & Alderson, A. (2020). Effect of steam conversion on the cellular structure, Young’s modulus and negative Poisson’s ratio of closed-cell foam. Smart Materials and

Structures, 30 (1), 015031. http://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/abc300

Duncan, O., Shepherd, T., Moroney, C., Foster, L., Venkatramam, P., Winwood, K., … Alderson, A. (2018). Review of auxetic materials for sports applications: expanding options in comfort and protection. Applied Sciences, 8 (6), 941. http://doi.org/10.3390/app8060941

Foster, L., Peketi, P., Allen, T., Senior, T., Duncan, O., & Alderson, A. (2018). Application of auxetic foam in sports helmets. Applied Sciences, 8 (3), 354. http://doi.org/10.3390/app8030354

[…] football. The introduction of Guardian Caps is a testament to the industry’s commitment to pushing the design envelope. These caps add a protective layer on top of the traditional helmet, absorbing shock and reducing […]

LikeLike